Author’s Note

This first ran on GameDeveloper in 2018. While I consider it evergreen it feels especially relevant now with the release of Baldur’s Gate 3. (And to a lesser extent, Armored Core 6)

I often write pieces that push back against conventional wisdom but I try not cross over into contrarianism. When pressed about his piece “Don't Play Untitled Goose Game” Ian Bogost admitted people should play it - that’s just trolling.

This is not trolling. Topics like difficulty and accessibility are often used as culture war footballs, but I’m treating accessibility as a game design (and sales and marketing) issue. It would be easy to write an “accessibility is good and if you’re against it you’re doing a gatekeeping” take, or an “accessibility is code for ‘wokified’ ” one, but hopefully I haven’t written either of those.

I’ve edited this reprint a bit more than usual for readability and to sharpen some points.

The Many Meanings of “Accessibility”

I often hear that lack of proper terminology is holding back game design and criticism. This makes less sense with each passing year and it was flimsy to start - it's hard to believe that new jargony terms are needed when we're so bad at using existing ones.

I can't count the number of times I've seen a walking sim described as "unique" despite using not only familiar mechanics (walk around, examine objects, read graffiti, listen to audio logs) but a familiar central story as well: explore the abandoned place and figure out where the people went. Or how often "core gameplay loop" is used to describe something that is neither gameplay nor a loop. "Everything is political" is a common phrase these days, but if everything is political then the word necessarily has no meaning. (One could just as easily state that "everything is ham")

Thanks to the work of advocates like AbleGamers there's been a strong uptick in the game industry's understanding of accessibility issues. But the game industry regularly uses "accessibility" to refer many distinct concepts, most of which are better described by other more specific words. Those concepts include:

Actual accessibility

Immediate Understandability

Approachability

Difficulty

Conformance to Preference

In this blog I'll argue for a narrow conception of "accessibility" while examining (and largely rejecting) other uses of the term.

Accessibility Meaning 1: Actual Accessibility

What I'm calling "actual accessibility" is the one related to disability and access. Making games more accommodating to people with disabilities is just a nice thing to do, and those changes often help everyone. Subtitles are useful when playing at low volume, for non-native speakers, or can rescue a game with sound mixing issues. (Such as in Xenoblade Chronicles X, where the music in cutscenes is regularly mixed too loud to hear the dialogue) Icons that look distinct not only in color but some other aspect are easier to pick out even for those without vision issues. It's up to each developer to determine the effort they put into accessibility but broadly speaking that effort’s a good thing.

This use of "accessibility" — the plain English meaning — is fairly new in games1. For a long time "accessibility" has primarily meant a mixture of lowering difficulty and "streamlining." A developer interview from a decade ago about making their sequel more “accessible” is almost certainly not about actual accessibility but instead about something like moving a game from PC to console and making it palatable to that audience.

Accessibility Meaning 2: Immediate Understandability

Disclaimer: when it comes to understandability, approachability, complexity, etc, there are accessibility issues related to cognitive functions. The following sections should be read as addressing "casualization," streamlining etc for the sake of mass appeal, while granting that those overlap with "actual accessibility." It's left to the reader to determine which sorts of streamlining changes are in service of genuine accessibility concerns and which are not.

We frequently use "accessible" to mean "streamlined" or "simplified." Why don't we just say that then? I'll suggest one reason here that I'll revisit later: "accessible" conveys a certain moral weight and importance; it's a word with a very positive connotation, when a term like "simplified" reads as neutral or negative.

If you're a Deus Ex 2 developer you probably don't want to say that your game has smaller maps and universal ammo because you think console gamers have smaller brains than PC gamers — that sounds bad! That the game is being "made more accessible" sounds good — who could possibly be against accessibility?

One downside of using "accessibility" as a euphemism is that gamers are now trained to roll their eyes and think "here we go again.” Not because those gamers are against actual accessibility changes (though…some are) but because they're against sacrificing core elements of a franchise in an attempt to broaden market penetration.

Is Immediate Understandability Good?

I’m opposed to using "accessibility" to mean "understandability" and I'm also not convinced that immediate understandability is even a good thing. At least, not across the board.

It’s wise to be wary of conventional wisdom, especially when delivered in slogan form separate from any original justifying arguments. There are two related conventional wisdoms I'd like to examine: "easy to learn, hard to master" and the idea that while depth is good complexity is bad.

Or take League of Legends. This game breaks so many rules of “good design”. It is a clone. It is over-complicated to the point of utter indecipherability. It is fussy, baroque, full of arbitrary, non-intuitive details (Last hitting? Inhibitors??). It makes no attempt to teach the player or draw them into its labyrinthian systems.

I certainly don't agree with everything in Against Design by Frank Lantz but the above point seems unassailable. (Well...minus the "clone" claim) And what's written above could apply to the entire MOBA genre or any number of Steam survival games.

Just as there are people drawn to tall dark mysterious strangers there are people who like coy games that don't readily reveal their mysteries of content and construction.

I often hear people use Street Fighter 2, one of the most popular games of all time, as an example of "easy to learn, hard to master." But Street Fighter 2 is not particularly easy to learn. Compared to contemporary arcade games it was much more complicated with virtually zero instruction. The game introduced concepts that, while well-understood today, were novel then: blocking by holding back, circular and charge motions, combinations enabled by hit stun, cross-up attacks, cancelable attacks. The game had six buttons at a time when most games had two.

Street Fighter 2 wasn’t intuitive or streamlined. Is was the polar opposite of streamlined, not "accessible" at all in the marketing-speak sense. What Street Fighter 2 was, however, was fun for people of all levels. It had great graphics and animations, detailed backgrounds and cool line-scrolling parallax foregrounds. It had catchy music. Even if you didn't know what you were doing you could pick Chun-Li and mash out some "wind kicks", or mash fierce punch as Guile to alternate (for a beginner seemingly at random) between a sweet backfist, a devastating uppercut and a suplex. It's not that Street Fighter 2 is easy to learn, it's that it's fun even when you haven't learned it. And many people never learn it, content to wiggle the joystick and mash buttons forever.

Similar to "easy to learn, hard to master" is the notion that depth is good but complexity bad. This is a meme-level proposition typically supported with meme-level arguments, usually analogies involving Chess. (The world needs another appeal to Chess like I need a hole in my head) There's a simple "proof of the pudding is in the tasting" counter-argument to the idea that complexity is bad: plenty of people like it.

League of Legends is extremely complex. Not only are there many rules but as in a collectible card game the distinction between rules and content is thin. To play the game at a reasonable level you have to understand dozens of characters and hundreds of abilities, and to play at a high level you have to understand over a hundred characters. As well as items, jungle monsters, XP formulas, non-intuitive ability interactions, and an increasingly complex rule set.

There's a notion that if a game is popular an "accessible" version of that game will be even more popular. But the streamlined version of League of Legends, Heroes of the Storm, is less popular. Maybe the right level of complexity for MOBAs is very high because breadth is a main reason people like that style of game. When Street Fighter 2 came out 8 selectable characters seemed like a lot. Now players complain if a fighting game launches with less than 20. They demand breadth.

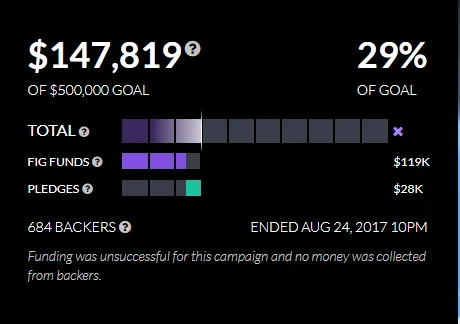

Every so often someone attempts to make a more "accessible" fighting game. Fantasy Strike didn't come close to reaching its goal on Fig and appears to be one of the worst-performing games on the platform. Rising Thunder was canceled while still in alpha. There doesn't appear to be high demand for streamlined fighting games, at least the non-transformative kind that subtracts complexity from the Capcom formula. (As opposed to a more transformative, more apples-to-oranges game like Nidhogg)

The belief that a streamlined game will have more mass appeal is for many a non-falsifiable religious one. When a streamlined game does well it's evidence that the theory is sound, but when one does poorly it's dismissed as an irrelevant data point. For every Monster Hunter: World - a simplified and successful entry - there's a Marvel vs Capcom: Infinite; the track record of games that have been made more "accessible" for broader audiences is very mixed. Often these games lose their built-in audience while failing to capture a new one. I installed the demo for Dawn of War 3, played the first tutorial and never touched it again, even though Dawn of War 1 is my favorite RTS. When I read that Marvel vs Capcom: Infinite was reducing team size and removing assists I was worried, and that worry proved justified — personally I'm not interested in a Simple 2000 Marvel fighting game and the new audience the streamlining was supposed to unlock never materialized. Few people seem happy with the simplification of multiplayer maps in Titanfall 2 or the weapon system of Destiny 2, or with the 2-gun limit of Resistance 2. For these cases and hundreds more you can claim that removing complexity is a solid strategy that was just implemented poorly. But then can't I claim that improved graphics and a seamless map are the reasons Monster Hunter: World did well, and it would have done even better had it retained more complexity from previous versions? Can’t I claim that increasing complexity is a great strategy and any counter-examples were simply poor execution?

Of course none of this means that all games should be needlessly complex or that obtuse UIs and unclear inputs are good. But I do think that "easy to learn, hard to master" is ultimately more a bumper sticker than a well-realized thought. Looking at Twitch popularity or Steam sales numbers I don't see any indication that "easy to learn" is a slam-dunk value proposition. If anything the PC games market often leans towards games that have more "needless" complexity and that are somewhat fiddly and baroque — towards "PC-ass PC games." (For example: Kingdom Come: Deliverance) Even the "hard to master" half doesn't look so solid in an age of "cinematic experience" content-tourism games that don’t demand much of players.

Not only is using "accessibility" to mean "immediate understandability" or "streamlining" not good word choice it also encapsulates an overvalued concept.

Accessibility Meaning 3: Approachability

If meaning 2 of accessibility is "easy to grasp" then meaning 3 is "apparently easy to grasp"; meaning 2 but from the outside looking in.

This meaning is based on apparent nature, so it can be a function of marketing rather than development. We see titles like Madden 2018 and Assassins's Creed: Origins instead of Madden 27 and Assassin's Creed 14 in part because those titles would indicate a buildup of mechanical plaque or essential narrative.

“Approachable" or "welcoming" captures the intended meaning here much better than "accessible." And as with understandability I'm not sure that apparent understandability is as attractive as we think it is, for the same reasons I'm not sure about understandability itself. So once again I'm opposed to both the word choice and the concept it captures.

Looking at the Steam Top 100 for 2016, by my estimation about half of the non-bronze titles have high apparent complexity. (I’m ignoring bronze purely for simplicity) The Stellaris description on the store reads “from the makers of Crusader Kings and Europa Universalis.” One of the first reviews reads "Stellaris is one of those games where you have to invest a lot of time and effort into learning how to play.” These are presented as selling points, not negatives.

In some sense by definition players want approachable games. But the games people want to approach may not be the games we typically consider “approachable.”

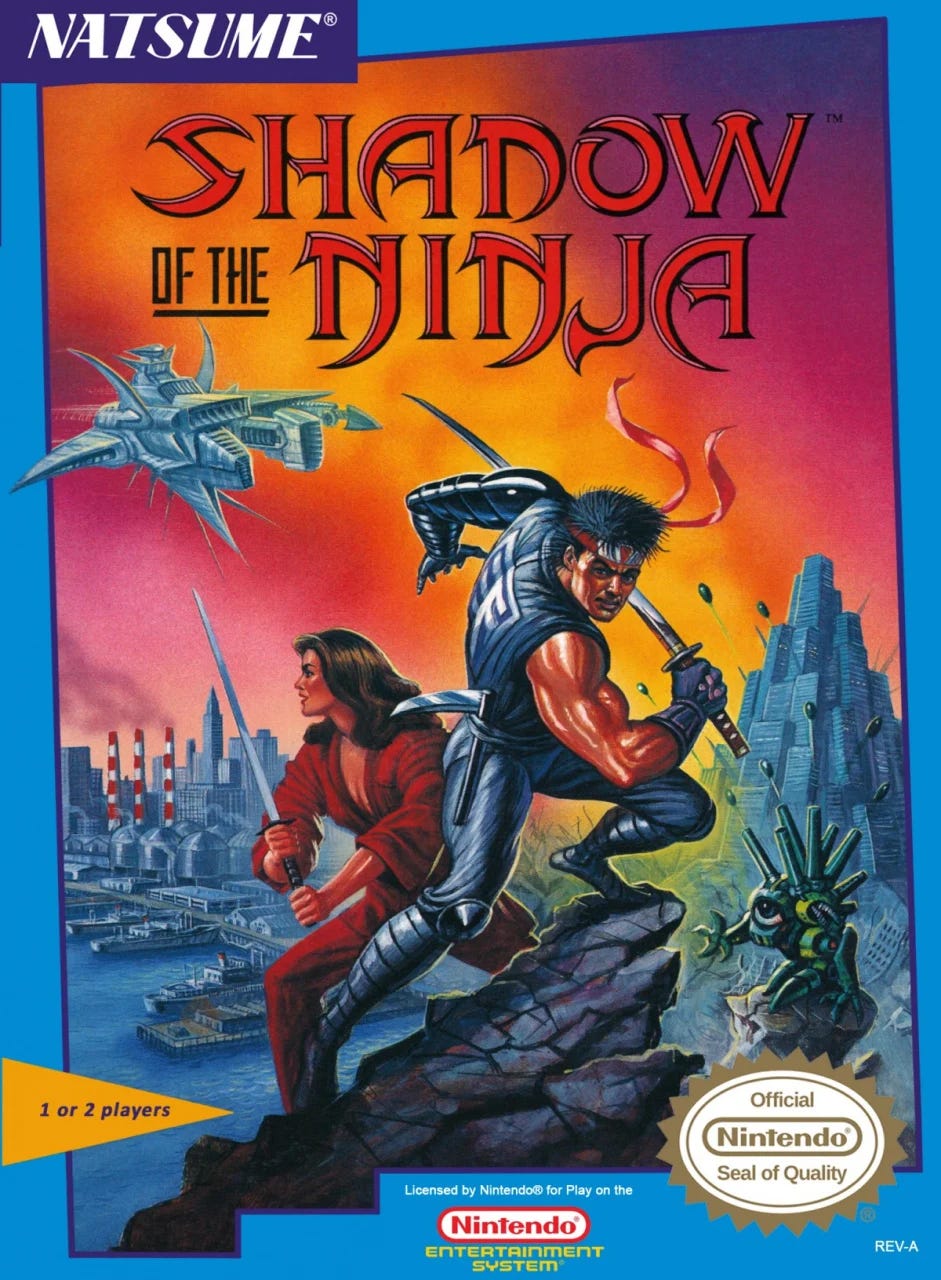

Especially for games with the potential for community, a baroque appearance can promise some fun communal problem-solving. Decades ago you might have heard the trick to beating King Hippo on the playground. In elementary school a girl lent me her copy of Shadow of the Ninja (a hidden NES gem) in exchange for an explanation of how to get past a gap in the sewer level of Ninja Turtles. (Just tap the jump button so that you don't bonk your head on the ledge above you. Get it together Kristina!) The modern equivalent is playing ARK with your friends online and sharing theories on how to best tame creatures or which items to craft first.

Some games foster community with multiplayer mechanics, but even a mostly single-player game like Dark Souls can foster community through lore and systems that encourage players to band together intellectually. I got over the hump in Dark Souls when my friend from out of state visited and helped me get a Black Knight Sword and defeat the Gargoyles. And for multiplayer games players who fumble through an experience together may end up appreciating both the experience and each other more, similar to boot camp or fraternity hazing. I've seen people remark that the Sea of Thieves beta had very little instruction but that’s often framed positively, as it encouraged players to work together and led to wacky high-seas hijinks.

So again: we shouldn’t use “accessibility” to mean “approachability” and approachability is probably overrated anyway.

Accessibility Meaning 4: Difficulty

There's a relationship between difficulty and accessibility though it's often oversimplified. Take a bullet hell game where the player can't see the bullets due to some visual impairment. In that case dramatically lowering the difficulty may make the game beatable but it doesn't address the real issue and delivers a very different, lesser, experience. In many cases difficulty has no bearing on accessibility at all: lowering the difficulty of a game doesn't help someone who has problems making out the dialog in cutscenes or who can't play the game due to epilepsy concerns. Accessibility guidelines encourage granular options and describe a range of disabilities; being bad at videogames is not a disability, though it can be the result of one.

It’s hard to object to optional difficulty tweaks, even as someone with contrarian leanings. While these topics may be contentious among fans or games media they aren’t particularly contentious among working developers. When Nintendo began introducing explicit helper methods in their games, starting with the Super Guide in New Super Mario Brothers Wii, there was an outcry from some corners but I sense only a small percentage of developers had any issue with it. The Mario games are made for all ages and the Super Guide is an opt-in way to help younger or less skilled players. Similar to the debate over ludology vs narrative, which is performed almost entirely by academics rather than working game developers, the debate for or against systems like the Super Guide is performed almost entirely by outsiders.

Unlike the overrated concepts of real and apparent understandability, adjustable difficulty has been historically underrated. (Difficulty options in older games are rare) And while there is a distinction between accessibility and difficulty they are at least related, so it's hard to object too strongly to the terms being intermingled, even if they aren’t synonyms.

Meaning 5: Accessibility as Catering to Preference

This section is going to based heavily on Now Ubi’s opened the door, can we have our “Skip Boss Fight” button?, so you should probably skim that before continuing.

There are two arguments made in favor of the titular button: one is that boss fights present an accessibility issue, and the other is that the author just doesn't like boss fights. These are unrelated and the conflation of personal taste with accessibility concerns does the piece no favors.

Accessibility guidelines are typically highly specific. I can't remember seeing "bosses" as an accessibility category. If I had to sum up accessibility guidelines in one sentence it would be "give people fine-grained control", and a button to skip bosses is the opposite of that.

It's hard to imagine that someone who likes boss fights but has a disability would be happy to skip boss fights except as a failsafe. If I lost my hand in a farm accident (don't laugh, it happened to my college roommate) I'd still want to do boss fights and have the same experience as other players, which might mean adjusting the difficulty downwards. I certainly wouldn't want to skip them entirely — losing a hand wouldn't make me also lose my love of boss battles.

The idea that skipping inaccessible content is an accessibility solution is strange. It's like telling your wheelchair-bound friend that the solution to a concert venue that's not wheelchair-accessible is to skip the concert because the band playing it is awful. That only makes sense if your friend didn't want to attend in the first place! Otherwise the solution is just the problem restated.

The piece conflates inclusiveness, difficulty and accessibility. "Gaming has always been inclusive"? Accessibility concerns in games are relatively recent — show me an NES game with a colorblind mode or an SNES game that allows you to tone down bright flashes. Games are historically non-inclusive of people with disabilities, which is why organizations like AbleGamers exist. Yes, some older games included cheat codes, but the Konami code is a hidden difficulty setting, not an accessibility setting. Using different words for different concepts is good.

The biggest weakness of the article is that accessibility and inclusivity concerns appear in the piece to prop up and add import to the author's personal tastes. The author wants a “skip boss fights” button because they don’t like boss fights, not out of deep empathy for disabled players,

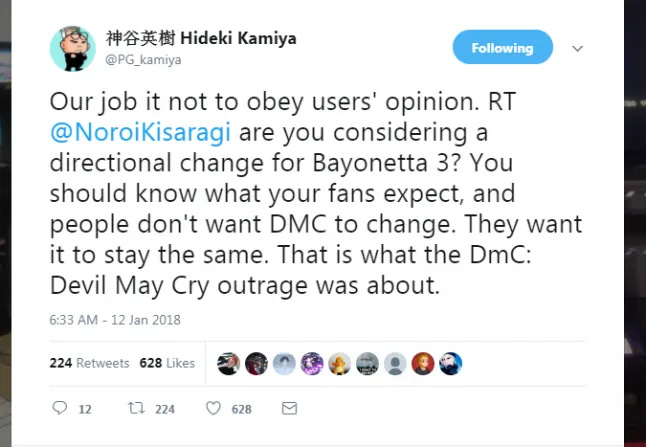

Providing accessibility options feels like a kind thing to do - there's some moral weight to accessibility concerns. There is, in my mind, no moral weight to preference concerns. Game development is a not a service hospitality industry in which the customer is always right. I've seen all sorts of wonky debates comparing mediums: well on a DVD you can skip the parts of a movie you don't like. Well in a movie theater you can't. All that nonsense aside, if you can't skip the parts of a game you dislike: you'll live. In an age of carefully crafted "we're listening to each and every fan" PR responses I suppose that's not something you're supposed to say but there it is.

To ignore accessibility concerns is to perpetuate de facto, if unintentional, discrimination. (That is why the Americans with Disabilities Act exists) "People who dislike boss fights" are not a historically oppressed people in need of redress and creating a product that people dislike is not discrimination. An accessibility issue is when someone wants to experience something but can't, not when they can experience something but don't want to. The way these two are intermingled in the piece, as if they are on even footing, only makes accessibility concerns appear trivial. To be as blunt as possible: if some disability prevents you from playing a game that's bad. If some preference prevents you from enjoying a game that's life. Accessibility is important in a way that preference simply isn't. They don’t belong in the same conversation.

Words: They Mean Stuff

There's a strong temptation to overuse weighty words and erode their meaning. "Problematic" is used to describe things that pose absolutely no problem to anyone. "Mansplaining" and "gaslighting" once both had real meanings; now they both simply mean "someone disagreed with me." The right uses "treason" to mean "unclapfulness"2 and "cultural marxism" to mean "anything I dislike."

Historically “accessibility“ was often trotted out as a euphemism for questionable streamlining efforts in the way that "VR content experience" is used in place of "short tech demo." But “accessibility” is increasingly used in a specific literal sense - that's a good thing. We already have perfectly good words to describe understandability or approachability or “things that conform to my preference.”

It's easy to consider only the most obvious accessibility cases: someone is colorblind or missing a hand. Expanding that to someone with a repetitive stress injury or chronic fatigue or whatever else is appropriate. I've seen suggestions that games that run poorly on old computers is an accessibility issue. Being unable to afford a new computer isn't a disability but it is literally access-limiting. So a wide definition of accessibility is good. What isn’t good is blurring the lines between accessibility, inclusivity, preference and marketing strategies, such that decisions to increase mass appeal are touted as accessibility, or that adding Burger King styled "have it your way" options are "inclusive" of people with strong preferences.

Addressing access and addressing preference can look similar but these are distinct concepts. “If you don't like it buy something else" doesn't work for people with disabilities as their issue is access, not preference. That line is fine, however, if someone just doesn't like the graphics on level three.

When I first wrote this some people disputed it, arguing that “accessibility” has always primarily meant “accommodating to people with disabilities.” It probably depends on what you were reading at the time, but I went back and found many examples of developers using “accessibility” to essentially mean “streamlining” or “consolification.”

This was in reference to conservatives being angry that Democrats didn’t clap at the State of the Union…I think

League of Legends isn't a clone?

"To ignore accessibility concerns is to perpetuate de facto, if unintentional, discrimination. (That is why the Americans with Disabilities Act exists)" Businesses hardly have the luxury of ignoring ADA regs. Moreover, ADA has less to many older downtowns being left to decay, as ADA requirements are too expensive. In other places, like NYC and SF, ADA regs have been weaponized by lawyers extorting businesses for non-conformance. But discrimination, bro. The road to hell is paved with good intentions