We're Struggling to Make Games

Western Game Developers Are Overmatched (don't kill the messenger)

This is not “games were better back in my day”, “I miss when games weren’t GAAS”, or “wokeness and DEI have ruined games.” This is not a lament over video game quality - I leave that in the capable hands of reactionary youtubers.

This is far more literal: we struggle to ship games within reasonable budgets and timeframes. When those games do ship - if they do ship - they often fail to reflect those resources in both craft and audience appeal. This is a lament over modern video game production woes.

Dragon Age: The Veilguard released ten years after Inquisition. Recently-shuttered Monolith Productions last released a game in 2017, and wasn’t far along on Wonder Woman. Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League was intended to capitalize on the Suicide Squad film - not The Suicide Squad from 2021, but Suicide Squad from 2016. I played Ubisoft’s Skull and Bones at an E3, I believe in 2018. It released in 2024.

Naughty Dog’s last game was The Last of Us Part II in 2020. Their next game is reported to release in 2027 at the earliest. Sony’s Bend Studio last released a game in 2019. Media Molecule’s most recent game was 2020’s Dreams. As far as I know they have no announced next project - I had to google to confirm they’re still in business. Bluepoint Games released Demon’s Souls in 2020 and has been quiet since.

Sony closed Concord developer Firewalk after one game. At the same time it closed Neon Koi, which never released a game. Deviation Games also closed before it released anything. Large swaths of Sony’s developers have effectively skipped a generation. (Before you object that Sony is a Japanese company, the gaming division has been run out of Europe as of late)

Western Woes

Video game development is volatile world-over, but this lack of productivity isn’t evenly distributed. Capcom is firing on all cylinders, releasing collections, remasters, remakes, sequels and new games on a regular cadence. Konami is back. When Nintendo takes a long time on games like Breath of the Wild or Tears of the Kingdom they do well critically and commercially - it’s evident where the time and money goes. Sega can make 8 Yakuza games in the time it takes Bioware to make one Dragon Age - that’s not hyperbole.

We regularly see successful games from upstart Korean or Chinese companies, or ones that have raised their profile and quality bar. Lies of P, Stellar Blade, Black Myth: Wukong, The First Berserker: Khazan, inZOI, Palworld, etc.

Concord cost over $200 million to make. It’s an arena shooter with 16 characters and 12 maps. It has no story mode and no set pieces. Overwatch 2 is a sequel that made a few rules tweaks, cut all the promised single-player content, and launched with a whopping three new characters.

Compare those to Marvel Rivals.

Riot Game’s League of Legends fighting game, 2XKO, just announced that it’s launching with 10 characters. It’s been in development since at least 2019. Fatal Fury: City of the Wolves started development in 2022, and just released with 17 characters.

When games take this much time and money to release (if they release at all) the pitch for a western-made game becomes untenable.

It’s Bad Management

Bad management is a well-explored topic by Jason Schreier and others, so I don’t feel the need to cover it extensively.

One aspect of bad management I’ll bring up, though, is the number of games and teams that, due to management, have almost no chance of success from the get go.

If there was ever a game begging for a “bigger, better, more badass” sequel it was Dragon Age: Inquisition. It significantly outperformed Dragon Age 2, marking a new direction for the series that could be milked (non-pejorative) for a few entries.

Instead it took Bioware a decade (granted, not all of it full production) to create a follow-up, and that follow-up almost certainly sold worse than a straightforward sequel would have.

Management didn’t plan on taking 10 years from the outset - that time was the result of a winding, fraught development. But, according to reports, a more straightforward Inquisition sequel was quickly ruled out or never seriously considered. Instead of a low-risk, medium-to-high reward approach, they opted for a high-risk approach. I didn’t write “high-risk, high-reward” - there’s no reason to believe their approach was particularly high-reward.

Sony’s approach to Concord was similarly high-risk dubious-reward. Say what you will about the quality of the game but an arena-shooter that cost $200+ million to make and includes no secondary monetization has a steep road to success. And, without impugning the quality of the game too much, it doesn’t scream $200 million.

Sometimes companies are set up to fail. This is particularly true of new companies that jump directly to “triple-I” or AAA production by hiring veteran, high-profile leadership teams attractive to investors.

In practice this means committing millions of dollars in salaries to people with job titles like director, creative director, narrative director, creative visionary, head of technology, and so on. Those jobs, when done well, can make a video game better, but they aren’t required to make a video game, and often they can’t make a video game. The people in those roles, if they can do hands-on development, have often graduated to management positions where they aren’t expected to.

These teams face a huge problem: on day one they have an empty Unreal Engine project file, on day 1500 they need the project file of a finished game, and they can’t make tangible progress towards that goal.

Prytania Media is one such example. This company spun up 4 different game development studios, using tens of millions of dollars of investment funds. All four of those studios have now closed without releasing a single game between them.

Fang & Claw used $3 million in seed money to hire a Studio Head, an Executive Producer, a Creative Director, an Art Director and a Technical Director / CTO.

Possibility Space’s first hires were for Visual Director, IP Director, Narrative Systems Design Director and Technical Director. I have no idea what an “IP Director” is supposed to do at a company with no IP. I’ve never heard “Visual Director” used as a job title in games. There’s a ceiling on how much meaningful work these roles can perform at a newly-formed company, regardless of how talented or industrious those hires may be, and the founders who spun up 4 studios at once were necessarily hands-off.

Similarly, while researching this post I came across a video from a Youtuber who was hired by Deviation Games in 2021 to serve as their community manager, and was laid off in 2023. Deviation Games never released a game and never announced a game, which really limits the scope of what a community manager can do!

There’s a raft of top-heavy, veteran-leadership companies funded 4-6 years ago that will never release a modest hit, or in many cases any game at all.

It’s Not Just Bad Management

Managers get paid to make the important decisions, so in that sense every failure is due to bad management. But sometimes “bad management” is an excuse, or at least, a woefully incomplete explanation.

Video game companies employ many managers, so one to blame is always in arm’s reach. Criticism of management is a bit inert when “management” can mean the publisher CEO, the studio head, the Creative Director or the Lead Writer.

When a team succeeds the credit doesn’t lie solely with management. So when a team fails it’s fair, at least some of the time, to spread the blame around a bit.

Perhaps it’s a gauche to write this now, when Company X just announced layoffs. But there’s no right time to write this, if that’s the criteria.

Some of You Have Odd Ideas about What Executives Do

Sometimes the CEO forces multiplayer games-as-a-service onto a game, only to change their mind three years later. Sometimes the CEO tells the team that his nephew loves Ninja Turtles so now your WW1 shooter needs Ninja Turtles. But C-suite members typically aren’t determining game content, authoring systems, designing characters, or even managing development schedules and budgets.

Many people blame “Sony meddling” for Concord’s1 failure but there’s no indication that Sony forced the team to make something they didn’t want to. Hermen Hulst probably didn’t design the characters or insist on the fearless-draft-style ranked rules.

No two people on any team have the exact same vision for the finished game, but the team seemed generally happy with what they produced, including the oft-criticized roster. An executive might issue an edict like “our game’s characters should reflect a diverse array of players” but they aren’t drawing the concept art.

I’ve seen some devs from the team unhappy with how the roster evolved over development, but the original and final designs are more similar than different.

The Saints Row team seemed happy with the direction of their latest game, pitching it as a more enlightened effort that would better connect with modern gamers. The team behind Dragon Age: The Veilguard seemed pleased with both the action focus and its more young adult tone.

We should blame “management” for approving Concord’s budget and for allowing the game to release without a secondary monetization strategy in place. (Yes, I’m basically saying executives should have forced MTX into the game, to give the game at least a chance to make money, though in this case it wouldn’t have mattered) It’s reasonable to guess that management was behind investing in CGI story vignettes, though that’s just a guess. But management didn’t write the off-brand Guardians of the Galaxy dialog or create Daw.

We tend to overestimate the amount meddling C-level positions do with game concepts. And it’s not uncommon for teams, not executives, to drive long development times and budgets.

Here’s Greg Zeschuk on BioWare working under EA.

BioWare co-founder Greg Zeschuk has challenged the common perception of EA as a controlling overlord forcing its studios to shoe-horn unwanted elements into its games, saying what EA really provides is freedom and resources - so developers can make their own mistakes.

…

"We had complete creative control over a lot of it; some fans didn't like some of it and some of it was experimental, quite frankly."

Sometimes “bad management” is giving the team too much freedom. Monolith Productions’ Wonder Woman game was reportedly struggling to incorporate the Nemesis System, first for enemies and then for allies. Neither use makes sense to me - the Nemesis System is a creative way to make randomly-generated, otherwise-repetitive enemies more memorable. A way of conjuring up worthwhile antagonists out of a white-noise sea of enemies. It’s an odd fit when you have named, well-established antagonists like Cheetah and Ares. Using it for allies means introducing a set of undistinguished allies - a solution in search of a problem.

Maybe Warner Brothers should have put their foot down and said “this doesn’t even make sense on paper, ditch the Nemesis System.” But had they done that both gamers and developers would have wailed - they have this great patented system that they aren’t even using!

Sometimes executives are too controlling, and other times not controlling enough. Those are both true at times. But that verges into tautological complaint. Maybe EA’s Patrick Söderlund should have dictated design elements of Anthem rather than letting the team work it out. But many would call that “bad management” - dictatorial meddling from someone only loosely involved in the game’s development. Letting the team figure it out for themselves - giving them “the rope to hang themselves”, as described by Zeschuk - is what most people would call good management, and what most game developers want out of an executive team.

Problematic Game Development Attitudes

Many of our development woes are at least part attitudinal - the result of stubbornness, dubious conventional wisdom or adherence to outdated norms.

“Making Games is Hard” or “Every Shipped Game is a Miracle”

Game developers telling the public - Amazon delivery drivers, single moms working multiple part-time jobs, etc - that their jobs are hard has always rubbed me the wrong way. It’s the job, it’s (sometimes) fun and engaging, and at least in the US it pays well. And if it’s hard…so what?

Being a line cook is hard. You make $17 an hour in NYC, it’s hot, and you get cut and burned a lot. As a cook half your dishes can’t “fail to materialize” if you want to stay employed.

I hear of both movies and games that every release is a miracle. Movies can spend decades in development hell as scripts, directors and actors come and go. But once a movie starts filming - in game terms once it enters full production - it usually releases. Rob Morrow, the lead actor on The Island of Doctor Moreau, quit on the second day of filming. Marlon Brando didn’t show up and director Richard Stanley was fired on day three. The movie still came out.

Comparing films to games has limited use, but movie-making works the way game-making is advertised to work but often doesn’t. Getting a movie to the point where it’s ready to film is a lengthy but low-cost endeavor. “Development hell” means paying one guy $40k to rewrite a script. Development hell in games means paying a full team millions of dollars for work halfway between prototyping and production.

I’m starting to think this is a chicken and egg problem. The longer games take to make, and the more development cycles are cancelled or rebooted, the more the job of game development shifts from shipping a game to filling a seat. You show up, do some good work - though there’s a good chance that work will be discarded, so who cares really? - and maybe a game eventually ships.

I’ve worked on multiple games that were cancelled for reasons that felt beyond my control, so I get it. But the more we believe that every shipped game is a miracle the more it’s true. Does the Yakuza studio think every shipped game is a miracle? I’m doubtful. Their approach seems more much workmanlike: every day you wake up and make the donuts.

On the Power of Iteration

“Making games is iterative” is true, but that’s morphed into the more dubious proposition that simply spending time is good. So many stories of development hell involve years of iteration in service of “finding the fun”, without much fun actually being found.

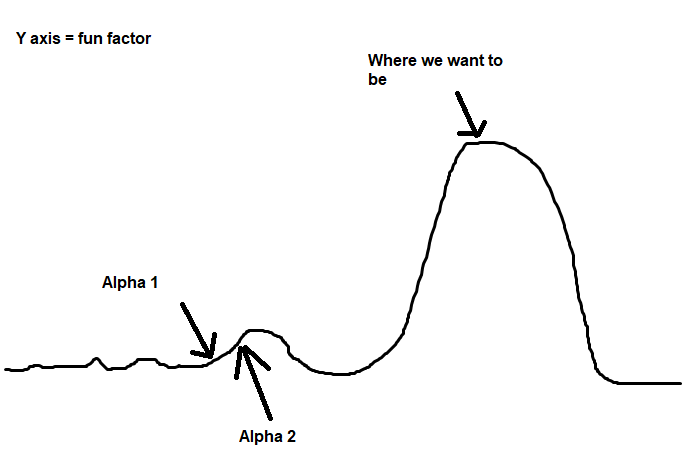

Sometimes iterating accomplishes little because you get stuck honing in on a local maxima. I see this in 2XKO. The second “alpha lab” was marginally better (or, according to some, marginally worse) than the first. The team is willing to experiment on the edges but not so much at the core - willing to tweak the controls but unwilling to rework them, for example.

2XKO, like many games that undergo protracted development, also faces a Duke Nukem Forever problem, where development is outpaced by the industry as a whole. I thought 2XKO was visually appealing when it was first revealed, but since that reveal we’ve seen DNF Duel, Guilty Gear Strive, Street Fighter 6 and Fatal Fury: City of the Wolves, among others. 2XKO looks worse than all of those games, and crucially it looks older than all those games.2

I found a 2XKO interview where the director says “we’re sharing this game very early - a lot earlier than you typically would do.” That interview is from August 2024. The game was first revealed in October 2019.

Reading between the lines of that interview it’s clear that some players found the controls too complicated, when simple controls were touted as a main selling point. I’m sure they did some smaller-scale playtesting but the first large scale reality check came 5 years into development.

It’s not uncommon for games to take so long to make that they and a sequel could have released in that same timeframe, had they been more schedule-conscious. Even if you believe in “finding the fun”, focus testing, “user validation”, market research, etc, I think you have to concede that there’s nothing quite like feedback from the buying public. See the glowing Death Stranding 2 previews that just hit, with their emphasis on the way the game iterates on the first.

“When it’s done” or “a delayed game is eventually good” has morphed into an embrace of indefinite timeframes. “A delayed game is eventually good” was never true, and it’s less true today than ever. Delaying a game to add some final polish can push a game from good to great, sure, but eschewing a schedule can result in games that take 8 years to make and still release under baked.

The most common sentiment I see from dev teams working through development hell is “we’re cooking.” It’s possible that Monolith’s Wonder Woman game was the most slowly-cooking-but-ultimately-delicious action game stew ever created. But it’s also possible - and probably more likely - that with another 3 or 4 years it was going to be a pretty good action game with an upper sales ceiling below God of War, based on a movie property that was last hot in 2017. To mix cooking metaphors, while they may have been cooking the juice wasn’t worth the squeeze.

Management drives the schedule, but lack of urgency is hardly unique to management.

Ignoring Sentiment and Spite-Driven Development

Developers of games like Concord and Assassin’s Creed Shadows are in genuinely tough spots. Complaints about the casts of those games often come from flat-out racists. There’s a good chance that someone complaining about “bad writing” in Dragon Age is reflexively anti-woke.

But the writing in Dragon Age probably is too sanitized, young adult, and anachronistic. The roster of Concord isn’t great - that’s a real problem. (The roster of AC: Shadows, and of Star Wars Outlaws, are fine - confusing!)

Battlefield 5 was mired in controversy about historical accuracy and the inclusion of women, but culture war fighting aside, the first trailer looked more like a modern-day alt-history game that a WW2 one. Many complaints were motivated by regressive gender attitudes - but also, it’s a strange trailer! I think it’s safe to admit that now without fretting over giving emotional aid and comfort to anti-woke types.

Ignoring reasonable feedback because it smells unreasonable is understandable, but it can lead to situations like Saints Row where seemingly everyone but the developers saw danger ahead. Sometimes developers cross into spite-driven development, doubling down on misguided decisions, or producing community management messaging that effectively sabotages their game.

(I had some examples here but I removed them as it’s touchy subject and I don’t like contributing to culture war bullshit. Use your imaginations!)

Good Old Fashioned Exceptionalism

As I covered in “Elden Ring Discourse Emergency Dispatch”, when the Japanese game industry appeared to be struggling there was no shortage of western analysis.

I attended multiple GDC talks where western devs eagerly diagnosed the problems with Japanese game development: close-mindedness, not playing western games like GTA, lack of technical prowess, outdated game design, to even how source control was organized.

Now that Western game devs are struggling, however, there’s little explanation beyond “bad management.” Problems that aren’t written off as bad management are either ignored or attributed to the game industry at large.

There are people saying “American games just suck” but they’re Youtubers, not developers. I don’t think we need devs to say “American games just suck” but “maybe we’ve fallen into some bad habits” seems appropriate.

Game Development is Getting Away from Us

Some time ago I posted the following on Twitter:

Feel like AAA studios are increasingly creating well-made bad games. Games where the programmers and artists and sound people and cutscene editors etc all did their jobs well, but the game itself has a fundamentally flawed concept, a mismatch between the IP and the execution, etc

This got 800 retweets and 6,000 likes. I have 300 Twitter followers so this broke containment in a big way.

I wrote this with the gaming equivalent of The Rise of Skywalker in mind: everyone doing a good job except those paid the most.

Today this rings less true to me, in both movies and games. Sony’s superhero films like Kraven don’t have a good concept or script, they can’t maintain a reasonable budget, and for whatever reason they can’t match lines to lips or do ADR well either. It’s not that everyone on those movies is unskilled, but the production has crossed some threshold. Marvel’s Secret Invasion series has plotting and conceptual issues, but it also has basic directing, editing and camera-work issues. Much of this is “bad management” but it’s not all management. Ahsoka has bad makeup and costuming. (Or perhaps, the lighting and shooting angles aren’t doing the makeup and costumes any favors)

So many movies and TV shows have impossible-to-follow night scenes, and it’s not because executives forbid the use of lights for night shoots. Directors and DPs have convinced themselves that uniformly dark and dull scenes look good.

I see shades of that in how Dragon Age: The Veilguard’s writing is less Game of Thrones and more Legends and Lattes. From inside the industry there’s a push towards young adult writing, though there’s no indication that players prefer it. (If anything, the opposite3)

When I watch Star Trek: Section 31 my thought isn’t that everyone except the bosses did a great job. My thought is that the ability to make a good movie has just gotten away from them. The western game industry isn’t at that point yet, but it’s moving there.

I don’t know what the solutions are, but acknowledging problems would be a good start. There’s an understandable reluctance to give an inch on anything culture-war related, but these days everything is culture war related.

We should take cues from developers who have timelines and budgets more under control, and those consistently delivering at a high level. Over time our professional conferences and information-sharing have become more about advertorial content and influencers building personal brands. I frequently reference conference presentations but they tend to be older, even though the pace of change should render them obsolete. But the typical modern GDC presentation is “Community Clubhouse Developer Summit: Breaking the Productivity Trap: Reimagining Game Development in the AI Era (Presented by Community Clubhouse)”

Perhaps rethink what game development is. Less a beleaguered creative expedition into the game design wilderness and more a group of professionals doing a well-understood job.

Instead of paying lip-service to prototyping and failing fast either abandon those strategies as unworkable in practice or do them for real. There’s a huge disconnect between how we talk up those strategies and how we execute on them. Failing fast beats failing slowly and painfully, sure, but there’s little discussion of practical, non-theoretical processes that enable it. Why didn’t Naughty Dog fail fast with The Last of Us Online? “Fail fast” is often more meme than methodology.

Of course it’s management that sets schedules and budgets - or refuses to set them. Management determines production approach. But we collectively determine best practices, even if we can’t impose them on our bosses. And many of us are bosses, if not the boss.

I honestly don’t like picking on Concord because the game itself is fine and it’s such fodder for youtube outrage artists, but it’s a well-understood case

The art style also changed from being a more “painterly” Arcane-style to a more traditional cel-shaded style

Fantasy fiction has successfully trended young adult for years, but I don’t any evidence of a similar trend in games and those audiences are very different

Concord was a hypnotically bizarre event to me, I started watching some of the Youtubers you mention out of sheer disbelief over what was happening, and a few weeks after, when it was all done, most of those Youtubers I moved on from. But there were plenty of people willing to be fair to the game, including on Youtube. Dare I say it when developers make good games; there are influencers that would fall over them themselves to recommend those games to their viewers.

Well put.

Totally disagree on the Concord concept art vs. execution though. Execution there is worse in every way, and needlessly so. It looks like a bad cosplay of the concept art. Yes in both cases the character is "of girth" and obviously wearing some sort of "upcycled" thing from a landfill. But. In the first the character's pose and bearing is heroic, if not aggressive. In the latter it is slovenly. The details in the first say "I made these modifications and repairs myself, and they do Important Stuff(tm)." The latter says "I just found this crap and strapped it together. Nothing matters."

The former is bulky and sturdy, the latter is puffy and ugly. The first is worn and scuffed from use. The latter looks like damage from abuse and neglect. The palette in the first is grungy, subtly muted. The latter looks like it was salvaged from a grimy play place in an off-brand fast food chain. The differences are subtle, yes, but that little tweak in saturation and drop in contrast between elements makes a huge difference, as it often does in artwork.

I could just keep ranting here almost indefinitely. All of these things I just ranted about were unforced errors. There are no conceivable technical limitations here.

These details matter. Character designs matter, because you're asking players to commit to endless hours of inhabiting those characters, projecting themselves onto them, letting the characters project themselves onto the player.

Nobody wants to play a slovenly character who doesn't take her job seriously and obviously doesn't want to be there. Let that personality reflect itself in your mindset as you play the game and what happens? You don't take the game seriously and you don't want to be there.

The whole lineup was like that. Nobody wanted to play those characters, so nobody found out whether the gameplay was "fine".