In my last post I talked industry takeaways from Expedition 33, with a focus on business and production issues.

In that post I wrote:

Video game business advice is typically paired with “of course you have to make a great game”, but with precious little focus on how to do that.

The standout element of Expedition 33 is not an innovative business strategy, choice of genre, or the result of market analysis and research. It’s that they made a great game.

A game that I wouldn’t make.

Of course I wouldn’t make Expedition 33 for many reasons: it wouldn’t occur to me, I’m busy with other things, it would take resources I lack. I’m not French. But the pertinent reason is that on paper Expedition 33 didn’t strike me as a great game. It’s the kind of design I shy away from.

This post is about what I learned from Expedition 33; more exactly, what I learned from being wrong about it.

“The Real Time Elements in Expedition 33 are Bad Design” - Me Six Months Ago

The reveal of Expedition 33’s battle system, in which players can completely negate damage via well-timed button presses, worried me. My gut reaction was that it probably wouldn’t work - that it would be unbalanced and dangerously destabilizing.

Before Expedition 33 released I’d been batting around my own idea for a tactics / strategy RPG with timed button presses for active defense or extra damage. (Think Fire Emblem x Project X Zone)

I hadn’t put much thought into the extra damage element - “adjust to taste” seemed good enough. But I’d put serious thought into how damage reduction should work. Here’s how I first approached it:

If a well-timed button press reduces damage by 10% the feature may as well not exist. 10% damage reduction feels irrelevant, and it doesn’t make sense to spend development time on an irrelevant feature. So low numbers like 10% are out.

If you’re going to reduce damage by 30% or 40% you may as well do 50% - it’s a nice round number and easy to understand.

Reductions like 60% or 70% seem odd for the same reason 30% and 40% do - might as well just say 50%. Extensive playtesting could reveal that, due to the particulars of your damage formula, encounter length and rate, consumables, etc, the sweet spot is a number like 33% or 62%, but I’d never start with those numbers.

My conclusion is that there are only three damage reduction numbers worth considering up front: 50%, 100% and almost 100%.

50% sounds very safe and “fair.” A 50% reduction is noticeable and worth doing, but it’s not overwhelmingly powerful - it would be a mechanic without being the mechanic. 99% is basically 100% but in my mind less exploitable - if combat grinds on forever the player has to eventually heal or switch strategies or do something.

100% reduction strikes me as dangerous. If the player is great at parrying and parries negate all damage then nothing else in the combat system matters. Defensive buffs are pointless when you’re already taking zero damage. Exploiting the elemental weaknesses of enemies that can’t hurt you is purely a time-saver.

At the highest level my concern is this: what if the player fights the final boss and can parry all of their attacks, so the boss poses no threat? That sounds lame as hell.

This is how I’d thought about my own (theoretical) game, but figured this applied to Expedition 33 as well. That it would end up being a unenjoyable degenerate case: a game that offers many systems, only one of which matters.

The Perils of Personality

So anyway that was wrong.

My initial thoughts had some validity - the real-time elements rendering other battle mechanics meaningless was surely a potential problem.

For some players the game is too easy. On the flip side, because active defense is so strong enemy damage is high to compensate, which means if you’re bad at dodging and parrying the game can be too hard. One of the most downloaded mods relaxes the timing on dodges and parries.

I’ve seen plenty of players point out these sorts of problems, so they’re real to some extent. But some percentage of players will complain about anything and the game was well-received. I think I have to concede that my fears were largely unfounded. If anything, some skill interactions and bugs could trivialize combat far more than parrying and dodging could.

I also think I have to concede that my initial negative assessment of the battle system largely comes down to that’s the type of person I am.

In terms of game design (and maybe just life in general) I lean reserved - I’m not terribly spontaneous or adventurous. In life that means coffee places quickly learn my order since I get the same thing every day. In game development that means I’m the type of person willing to say that an idea sounds bad and we probably shouldn’t try it; which is, I think, a valuable type of person to have, but an entire company composed of me would be miserable.

I’m wary of imbalances and exploits. Exploits can ruin a multiplayer game for everyone. In single player games they’re less important, but players can still ruin a game for themselves by relying on an exploit or oversight, then blame the developer. It’s tempting to retort with “you control the buttons you press”, but some players will choose to press buttons that break the game, then bemoan the lack of challenge.

I lean towards mechanically subtle and sophisticated rather than big and bold. In Dark Souls you can follow a parry with a context-sensitive, hugely damaging attack. In Sekiro a parry depletes an enemy’s poise, which you have to do multiple times before you can deathblow them. There’s an even more restrained version of that though: do we need the deathblow at all?

In Street Fighter 3 there’s no poise meter and no deathblow mechanic. A parry negates damage and recovers quickly, which allows you to damage the opponent, but it’s up to you to maximize the damage based on the scenario.

One could imagine a version of Sekiro where breaking the enemy’s poise makes them briefly reel and it’s up to the player to determine and perform the maximum damage conversion - to open the biggest can of whup-ass. That’s a more subdued version of a death blow mechanic - less binary, more skill-intensive, more technical and finnicky, but less splashy than a canned animation where you slice a guy’s head in half.

Expedition 33’s total damage negation on parries and dodges is a dramatic feature - very splashy, in-your-face, strictly binary. The kind of feature I’m not naturally drawn to.

A Battle System Re-Analysis

When Expedition 33 released to acclaim I challenged myself: instead of poking holes in the system can I “steelman” it - can I make the argument that it’s a good system, and poke holes in my previous hole-poking?

One of my main objections was that if players can parry consistently then other aspects of the game barely matter. If the game is horribly broken and players can mash the parry button to parry every attack then yes, the battle system is fatally flawed, but that would be a bug, not a design problem.

We should design this battle system such that most players can’t parry enemies consistently right off the bat. Maybe the first time they fight a new enemy type they parry 15% of the time, then the next encounter is 20%, and so on.

If the threat of failing parries is real - and it should be for most players if we balance the game properly - then defensive buffs matter, and using offensive options to finish fights faster also matters. This is especially true due to how consumables work. In older Final Fantasy games you can load up on hundreds of potions and heal to full at the end of a battle - the damage doesn’t stick. In Expedition 33 consumables have a low fixed count and only refill at checkpoints (Estus Flask style), so using potions is attrition. Reducing damage by finishing fights faster or via defensive buffs lowers that attrition.

With practice maybe players can parry an enemy 100% of the time. But is that a problem? In most RPGs you can grind for experience and gold to make fights easier - repeatedly fighting an enemy and gaining proficiency is also “grinding” but it’s the player increasing their prowess rather than the characters. If anything that seems preferable - instead of accumulating meaningless video game stats the player improves a real life skill. Not a particularly valuable or transferrable real life skill, but a real life skill nonetheless.

Earlier I wrote:

What if the player fights the final boss and they can parry all of their moves, so the boss poses no threat? That sounds lame as hell.

That could be lame as hell. But also it could be cool as hell. If the boss is throwing out long attack strings and multi-hitting moves and the player, through practice, can deflect all of them: good for them. “What if the player gets good at the video game?” That seems ok.

Most single-player games can be trivialized with enough practice and skill.

On Important and Loud Features

At this point my objections to the system have fallen away. But I haven’t made an affirmative case - total damage negation might not be problematic, but why might it be preferable to say 50% damage reduction?

I think the answer is that, while I’m not a big believer in “unique selling points”, games need to stand out. They need to answer the question “how is this better or different than other games?”, or at the most basic level, “why buy this?”

Real-time blocks and parries negating all damage is a standout feature. Were the damage reduction more conservative the real-time elements would be a tertiary feature - the same tertiary feature that’s appeared in games for at least 30 years.

I often think about features in terms of tier and amplitude: how important a feature is and how loud that feature is.

Many games feature inventory management but in Resident Evil games inventory management is a central feature - a tier 1 feature.

Loud features are highly visible. They tend to be important features but I think these are different concepts. Street Fighter 6’s Drive Impact is the most visible, splashy, back of the box feature, but for skilled players it’s less integral than Drive Rush. Early Guilty Gear and Tekken entries featured instant-kill moves and ten-strings, respectively, both of which were back-of-the-box features but mostly irrelevant after a few hours of play.

Loud features are the features that set a game apart at first glance, and important features set it apart in the long run.

In Expedition 33 the parries and dodges are both important and loud. They appear to be a defining element of the game, and they are.

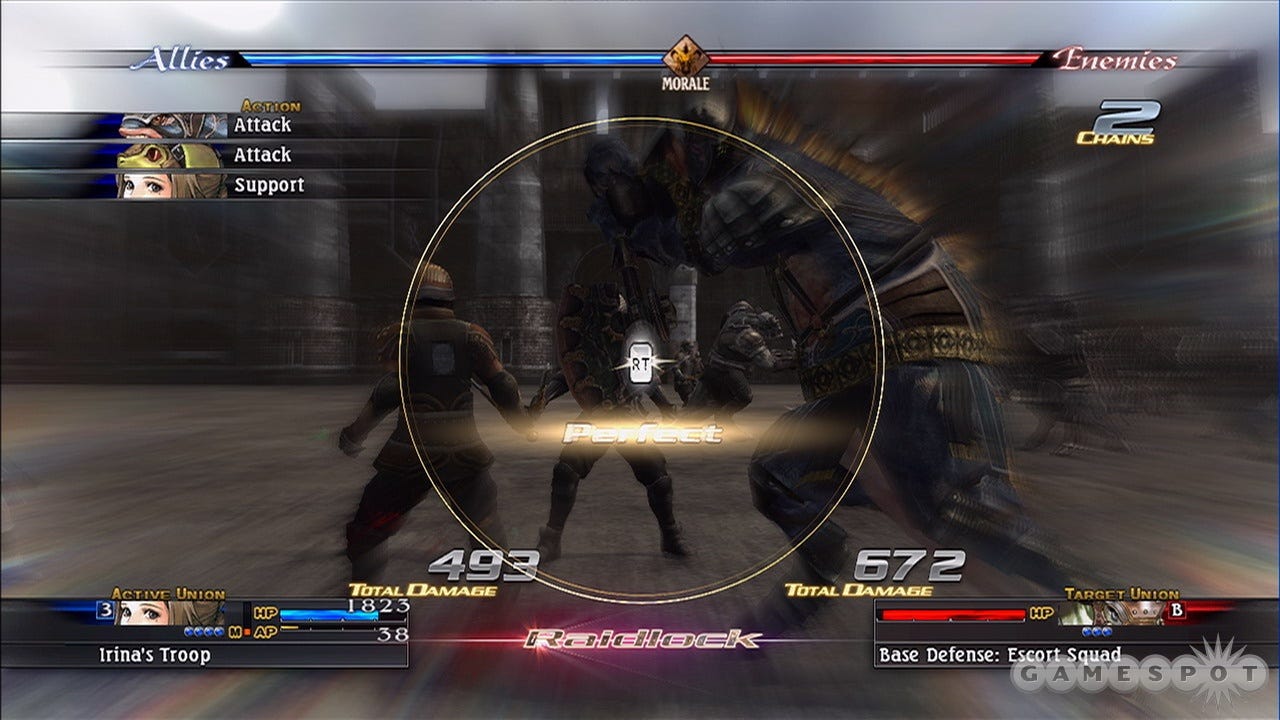

Active defense in turn-based games is hardly new. The Last Remnant has it, Sea of Stars has it. Super Mario RPG has it. What’s new about Expedition 33 is that well-timed button presses are the central battle mechanic, not a secondary one.

In Sea of Stars a well-timed block reduces damage (halves maybe?) but doesn’t negate it entirely. Well-timed attacks and blocks don’t look and feel impactful, backed by only modest sound and VFX work, which communicates a lesser importance, regardless of numbers. (The notable exception here, at least in the demo, is the boomerang weapon, which will satisfyingly bounce many times with well-timed presses)

The Sea of Stars battle system has competing elements with more visual and seemingly mechanical weight. You can interrupt planned enemy-attacks by breaking locks floating above them, and can collect energy orbs to power up your attacks.

Well-timed button presses in Sea of Stars aren’t the system, they’re just a system. I’ve seen suggestions that Expedition 33 would be a better game - more well-balanced - if dodges and parries were less powerful. Even if that’s true - which is down to taste - the game would have less to hang its hat on in that case.

High-amplitude features are memorable and serve to differentiate. Sandfall Interactive has copped to doing some light trolling with some features, like the platforming, which is arguably memorable in a bad way. But players can not only tolerate but enjoy memorably bad sections, as long as those sections don’t stretch on for too long. See the poison swamp levels in FromSoft games.1 The infamous Turbo Tunnel in Battletoads is remembered fondly, and the game probably would be as well if everything past that point weren’t equally maddening; the last 90% of Battletoads is all metaphorical poison swamp.

Raising the amplitude of features can mean higher highs and lower lows. That’s preferable to consistent blandness, and in some cases low lows don’t particularly detract.

In terms of practical production, the more central and obvious a features is the more a developer is incentivized to make it good. The well-timed button presses in Sea of Stars aren’t terribly important and they aren’t particularly satisfying - I don’t think that’s a coincidence. In Expedition 33 they’re more satisfying, and they need to be, as they’re the central mechanic. The puzzles in Silent Hill: Shattered Memories are easy to the point of barely being puzzles, but that’s ok because it’s not a puzzle game, just a game with light puzzle elements. The puzzles in The Witness have to be good for the game to work, because it’s a puzzle game.

In game development it’s much easier to polish visible features. In my experience it’s common to add clarifying UI, sound and visual effects to a system2 - to make the system and how it works more obvious - and immediately spot improvements or problems. Sometimes after making the effects of a system more obvious you realize the system didn’t work at all! In many older RPGs certain stats don’t work as intended or don’t do anything.

What I Learned From Expedition 33

What I learned from Expedition 33 is not “RPGs are more engaging with real-time elements” - I’m not a fan of blanket game design rules or turning food for thought into lessons learned.

I did gain appreciation for “crank up the waveform on features.” Raising the volume on features isn’t a new tool, but it’s one I might reach for quicker. I probably underestimate to what degree loud features can make games more fun and more marketable. I can recall a specific example of this: I was talking to a Starbucks employee about a game I was working on where you play as various animals. He asked about the craziest creature you could be, prodding me to say something like “giant fire-breathing dragon”, but my answer was more like “turtle.” He wanted to hear a splashy selling point, while I was concerned with more mundane matters like that a dragon might be too big to fit through a door.

So there’s that.

But the most important thing I learned was about myself.

There are good reasons to be wary of Expedition 33’s combat design. But my wariness was less rational than gut reaction - I just enjoy spotting potential problems and downsides more than I enjoy spotting potential opportunities and upsides. My biggest takeaway is that I could stand to be less like that.

Much of the criticism I see of Expedition 33, especially of the battle system, comes from those who are proudly old-school, conservative about game design, or who are prone to pessimistic over-intellectualization. Less thoughtful critique than “bah humbug.”

To those people I’d suggest the exercise I tried: instead of dwelling on the flaws of a system try focusing on the upsides. Delve into how it could go right, in terms of attracting players or providing a standout experience, rather than how it could go wrong. Instead of brainstorming ways it could fail brainstorm ways around those potential failures. You don’t have to Stepford Wife yourself into blithely accepting any feature proposal, but at least try on that way of thinking.

More broadly, game developers can be stuck in their ways for not-entirely-rational reasons. The designer who rejects special move motions out of hand, or rejects “modern” controls out of hand. The developer opposed to any randomness or asymmetry in games, not because it’s less fun or strategic but for dogged ideological reasons they can only explain via essay. The guy who accepts anything as long as it satisfies the “rule of cool”, or the guy who rejects fun ideas because “we don’t use the word ‘fun’ here.” Having a point of view is valuable, but that can cross over into stubbornly clinging to a shortcoming.

I wouldn’t call these sections bad exactly but they’re at least a pain in the ass by design

This can be visualization intended for the end user, or debug visualization like onscreen text printouts line drawing

>That could be lame as hell. But also it could be cool as hell. If the boss is throwing out long attack strings and multi-hitting moves and the player, through practice, can deflect all of them: good for them. “What if the player gets good at the video game?” That seems ok.

The first time I played Sekiro I had trouble letting go of old habits from Dark Souls/Elden Ring, struggled to get to the final boss, and then got my ass handed to me enough that I gave up. A couple years later I tried it again and, probably because I'd retained some muscle memory from my first try, got really good at it. When I made it to the final boss I beat him in two tries and felt like an absolute god, probably one of my favorite gaming experiences ever.

I wonder though whether "press button at the right time to block all damage" is a big enough mechanic to be central to a JRPG in the first place. I haven't played it so can't comment from experience, but it does not seem like something that would hook me.

Love me some perfect blocks and evades in Monster Hunter, but those are a small piece of a much bigger picture that makes the action, which is the central feature of the game, endlessly engaging. Combat in JRPGs is generally more of an unwanted chore, which maybe is something that needs fixing, but plucking a few mechanics from action games has never solved it for me.