What We Can - But Mostly Can't - Learn from The Success of Expedition 33

Part One of a Two-Part Special Event

Games that perform beyond expectations (in either direction) get turned into teachable moments. Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 is not only a breakout hit but slots neatly into existing industry discourse: this is how westerners are fixing the JRPG genre, or this is how western AAA devs need fixing.

These learnings can be convincing in the moment, but are often fleeting or contradictory. Clair Obscur benefits from compactness, but Baldur’s Gate 3 benefits from being stuffed with content. These are both valid observations but taken together present no neat lesson.

In this post I’m going to cover the difficulty of developing meaningful takeaways from the success of Expedition 33, something I admittedly enjoy doing. But while I don’t think there’s anything to learn from the success of games like Flappy Bird I do see legitimate takeaways from Expedition 33, so I’ll propose a few of those. In the follow-up post, tentatively titled What I Learned from Expedition 33, I’ll discuss a very specific way that it adjusted my attitude on game design.

What We Can Supposedly Learn from Expedition 33

I’ll start with a post from the popular GameDiscoverCo newsletter, Clair Obscur & Drive Beyond Horizons: subgenre + execution = hit!

This post identifies three reasons Expedition 33 succeeded:

Clair Obscur picked a counter-intuitive & undersupplied subgenre: there’s been few AA+ turn-based RPGs made by Western devs, except a handful of retro titles like Sea Of Stars.

…Its ‘look and feel’ are closer to the Western mainstream than Asian competitors

…

The game ‘threaded the needle’ for global appeal, esp. in China

That last point - that it did well across the globe - is less a reason for success and more the definition of success: the game did well because it sold well everywhere.

There’s no explanation for why it did well globally or especially well in China. Was the Chinese voice acting great? (Does it even have Chinese voice acting?) Did the game have a Chinese publisher that did…something? Was it designed with Chinese audiences in mind, or do the themes and gameplay naturally appeal to Chinese players for some reason?

On the point about Western look and feel: I do think there’s something to the art style of Expedition 33 that I’ll get to later, but I don’t think it’s as simple as that “anime aesthetic” is a turn-off. Genshin Impact has made 6 billion dollars!

On that last point: “Clair Obscur picked a counter-intuitive & undersupplied subgenre.”

Is JRPG an undersupplied subgenre?

The claim here seems to be that JRPG is a genre (though surely JRPG is a subgenre of RPG) and that the subgenre is “AA+ turn-based RPGs made by Western devs [excluding retro titles].” This seems like a cheat to me - when you get that specific nearly every subgenre is thin on content. There are dozens of super hero movies but only three about a guy who’s ant-sized - is the ant-sized hero an undersupplied subgenre?

At the highest level, “subgenre + execution = hit” strikes me as meaningless. Every game can be placed into a subgenre, which leaves us with “execution = hit.” Which…sure.

The section on Expedition 33 ends on this:

under-developed subgenre + great narrative & art direction + lean, focused team + smart gameplay execution = big hit.

Many top-sellers aren’t in under-developed subgenres. Assassin's Creed Shadows, Oblivion Remastered, MLB The Show 25, Call of Duty: Black Ops 6, etc etc.

Maybe the lesson here is that great execution in an under-developed subgenre equals big hit, and great execution in a well-developed genre also equals big hit. In that case the lesson is “make a great game.”

It may seem like I’m picking on this post, but this is what most business analysis of Expedition 33 reads like, and more broadly what game industry business analysis usually reads like.

The Big Problem with Business Lessons

Video game business advice is typically paired with “of course you have to make a great game”, but with precious little focus on how to do that. This type of advice is aimed at people who don’t have a craftsman’s eye and don’t sweat the details.

As a budding director Sinners might broaden your horizons about the use of music in film. It could introduce you to a new shot composition, or something technical like a lens type. These aren’t “lessons” exactly but they’re elements of craft you can carry forward in your own work.

Film execs, on the other hand, want to learn lessons like “vampires are in!” Sony thought the lesson of Venom’s success was “people like Spider-Man anti-heroes” so they made Kraven and Morbius. (A vampire movie and a Spider-Man anti-hero, how could it go wrong?)

These high-level strategy lessons are the easiest to summarize in executive-friendly bullet points, easiest to digest, easiest to act on, and don’t require much product knowledge. “You need great narrative and great art direction and smart gameplay” is hard advice to act on if you don’t know much about video games or what makes them good, but “battle passes are in” is something anyone can understand and act on.

As such it’s tempting to treat “and you have to make a great game” as a lesser concern. But the video game audience is discerning. That’s been one of Microsoft’s constant woes. Games like Halo: Infinite, Redfall, Starfield and Crackdown 3 are on-trend and check the right genre / feature boxes, but just aren’t that good. “The people crave Left 4 Dead games” might be true but the 17th best Left 4 Dead-style game is a non-starter.

The Wisdom in Ignoring Existing Lessons

One of the most common pieces of business advice is that you should make a game in a lucrative genre - either a genre that’s currently big on Steam (simulation, for example), or a genre that appears underserved. I don’t think JRPG fits either of these criteria. The writeup I cited above alluded to this by calling the sub-genre “counter-intuitive.”

Another common wisdom is that making a game at the intersection of genres is a bad idea, because the potential player-base will be the intersection of those genre’s fans rather than the union. JRPG fans might be turned off by Souls-like elements, and Souls-enjoyers might balk at JRPG elements. By mixing genres you also run the risk of not delivering what players expect, or by setting confusing expectations.

This advice sounds like a warped version of the useful observation that making a game that offers disparate play styles is tough to pull off. When these games succeed it’s often because they’re more than the sum of their parts - neither the combat nor town-building in Actraiser are best-of-breed but the game works as a whole. It’s easy to see where this can go wrong, when a game simply is the sum of its parts, or is dragged down by the lesser elements.

Alternating genres isn’t the same as merging genres - Expedition 33 doesn’t alternate between JRPG and Souls-like, it offers one primary mode with elements of both. And the notion that it’s wise to avoid offering disparate genres seems outdated to me anyway, given the number of games in form of “farming plus dungeon crawling”, “base building plus exploration”, etc. Grand Theft Auto is alternately a shooting game, a driving game and various mini-games. (Though they’re all presented as part of the same 3D world rather than as independent modes, I suppose)

A final bit of conventional wisdom that Expedition 33 bucks is that it doesn’t have a “unique selling point.” In retrospect you can claim that the French nature gives it a certain je ne sais quoi, but 2 years ago “the unique selling point is that it’s French” would have drawn laughs. It has real-time combat elements but so do Mario RPG, Sea of Stars, Lost Odyssey, etc. You can get into the mechanical weeds - instead of a stack of items you have a fixed number of refillable consumables - but that’s smart design, not a back-of-the-box feature. There’s no game that has its exact combination of art style, music, story, etc, but that’s true of all games. That’s not a unique selling point in the same vein as Cuphead’s presentation.

Lessons Learned as Biases Confirmed

I’ve read much analysis of why Kamala Harris lost to Donald Trump and in nearly every case the purported takeaways are the result of motivated reasoning to reinforce existing world views.

Some Democratic pundits and consultants blame “the groups” for Harris’ loss. They don’t blame Harris’ policies because they agree with those policies, or Harris’ advisors because those advisors are part of their social circle.

Critics of Gen Z blame Gen Z voters. (Or non-voters) Those who dislike boomers blame boomers. Those invested in identity issues fixate on how Democrats slid with Hispanics or Asians, or blame white male voters for lurching right. “Manosphere” trackers blame the manosphere and the lack of a “liberal Joe Rogan”, those invested in Palestinian rights blame Biden’s Gaza policy. Centrists believe the campaign should have appealed more to centrists, when appealing to centrist voters was the main strategy.

Few of these people learn lessons that contradict their existing beliefs.

People who think the game industry is guilty of gatekeeping believe that “hire people off of Reddit” is a lesson to learn from Expedition 33. Those looking for funding for their own “counter-intuitive” genre entry see Expedition 33 as evidence that we should fund those games. The guy who rants about games designed by committee credits the success to a singular vision, while the one who rants about bloated teams praises Sandfall’s catlike agility. The person who dislikes the typical JRPG credits the game with breaking away from that formula, and the person who likes the JRPG credits the game with borrowing elements of that formula. Expedition 33 has been held up as both an example of western developers besting Japanese ones, and by comparison as an exemplar of the slide of western developers.

Of all this sort of analysis (both political and video game) I’d ask the following: is it a lesson learned if there was no change in belief, and the lesson is simply “I was right all along”?

A notion reinforced still has value, but most people are eager to reinforce their existing notions, so that value is limited.

On The Incredible Productivity of 30 (plus or minus 382) People

Perhaps the biggest topic of Expedition 33 discussion is the push and pull over the claim that Expedition 33 was made by (a core team of) 30 people.

On one extreme some argue that since the core team is 30 people that the game was “made” by 30 people. On the other extreme are those who think the four Oboe players in the orchestra count as game developers and “made” the game as much as anyone else.

To me this is like debating whether craft services workers (the people who set up lunch spreads on film sets) count as “filmmakers.” It’s a purely definitional argument that film folks don’t debate because a) they all know what craft services does, and b) films use real metrics like budget and shooting days, not head count.

Video game analysis often uses poor metrics because those are the only metrics available. We use concurrent user counts or Twitch viewers in lieu of sales because publishers are stingy with sales data. Business analysis is focused on Steam because Steam metrics are easier to come by.

Head count is a metric we use to assess developers because we aren’t privy to real metrics like budget.

Ubisoft owns motion capture studios, so in an Ubisoft game the people who provide motion capture assistance are part of the team. Sandfall Interactive rented1 a motion capture studio, so the workers at that studio don’t count as “core developers.” But in both cases the games use motion capture that came out of a budget.

Paying a “core team member” takes money. So does paying a contractor or an outsourcer to do the same work, buying assets, renting out motion capture studios and so on.

In his video on Expedition 33, Youtuber Skillup asked if the budget was under $10 million and didn’t receive an answer. Clearly the budget wasn’t Spider-Man 2’s $300 million but “how did they do this on that budget?” isn’t a good question when we don’t know that budget.

Game Developers Can Be Very Productive

Given the amount of doom and gloom in the game industry (which I contributed to in my last blog post) it’s easy to adopt a broad “everyone just sucks at making games now” attitude. But game developers can be very productive in the right environment.

Revenge of the Savage Planet2 was also made by about 30 people. It got a bit buried (in part because it released two weeks after Expedition 33) but it’s well-made and arguably bigger in scope.

I’m not sure how many people work at Bokeh Studios, who recently released Slitterhead, but it seems same ballpark at least. When I fired up the demo I expected to be met with jank, but it’s a polished experience from the start.

Neither of these games captured the public like Expedition 33, but Sandfall isn’t lapping these teams in terms of raw productivity. Clearly Sandfall overachieved but I don’t think they’ve discovered a double XP hack.

Instead I’d propose the following: at some game studios an engineer might spend half their time in meetings, Slack, emails, etc, while the other half is spent on work that’s ultimately discarded. At another studio an engineer can spend their whole day working on content that appears in the shipped game. In those scenarios a “10x” engineer (or more) is very plausible.

Some companies don’t value productivity, don’t work to create environments where it can flourish, or expect and then receive low productivity. Or effectively sabotage production by re-litigating old decisions, re-doing work, reversing course only to reverse again, etc.

That some companies don’t value productivity sounds like a bold claim. But take Microsoft’s use of contract workers on games like Halo. That’s a decision to save money at the cost of lower productivity and quality.

Or take Double Fine Productions. Their top-down design philosophy often sees workers spinning their wheels waiting for directives from Tim Shafer. They realized this was a problem enough to hire someone to fix it, then fired him in part because they weren’t committed to fixing it3. Maybe this approach works for them, and with a more bottom-up approach they’d end up making generic action platformers rather than memorable ones. But it’s an approach that ranks productivity below other factors.

I don’t know much about Expedition 33’s production process, despite looking, so I don’t have a concrete takeaway here. But I’d note that the early demo of Expedition 33 looks a lot like the finished game. Visually it’s rough, with placeholder graphics and constant camera twitching. The plot and locations are different. But the bones are there.

According to James Gunn the biggest problem with the movie industry is that “people are making movies without a finished screenplay.” Even though most in Hollywood would agree that you should finish a script before filming starts.

Everyone knows that making a prototype that demonstrates the game then building that out into a full game is a good process. But maybe a lesson here is “actually do that though”, because so many games don’t follow that process. It’s hard not to side-eye games that, after 4 to 5 years, are still “struggling to find direction.”

Game developers can be very productive in the right environment. Three years into a project and still debating what sort of game you’re making is decidedly not that environment.

What We Can Learn

I enjoy poking holes in “what we can learn” analysis, but I do think there are real things to be learned from Expedition 33.

An Optimist’s Approach to Engine Use

Expedition 33 is an Unreal Engine 5 game, but lots of games use Unreal Engine 5.

It’s possible that Sandfall used Unreal Engine in novel ways, but according to this writeup their use was pretty standard: they used blueprints to wire up logic and Niagara for VFX because those are the standard built-in Unreal tools for visual scripting and VFX.

A couple uses stand out as minorly notable. One is that they used Sequencer (Unreal’s cinematic authoring tool) for skill animations. That’s a choice not all studios would make, instead authoring all the pieces (VFX, animations etc) separately and combining them via callbacks or animation events rather than editing them on a shared timeline.

The second notable use of Unreal features is the use of Metahumans, including for facial capture. I’m sure some teams, especially a few years ago, would have written the system off as not production-ready, too limiting, or too foreign.

Eternal Strands is an Unreal Engine game made by a medium-sized team - its character conversations use static portraits. Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown does likewise.

Cutscenes in Redfall are often animatics - motion-comic style presentations where static images slide across the screen. Even playback of found footage is delivered this way, which is jarring since you’d expect found footage to reflect in-game graphics and animation.

Maybe Metahumans and metahuman face capture weren’t quite ready when these games were made, or maybe the teams were reluctant to use it. (Or maybe it’s harder and more expensive than I think.) You could call animatic use an artistic decision but I think that’s often cope, to be frank.

Animatics usually look cheap. Animated models and face capture add a lot of apparent production value for relatively low-cost, if you’re capturing faces with an iPhone and not fancy equipment.

More than specific feature use, though, it’s clear the team adores Unreal Engine. It’s easy, especially with experience, to see the flaws in game engines, and easy to blame engines and tools for production woes.

This team was willing to be early adopters, to use what Unreal gave them, and didn’t suffer from “we have to build it ourselves” syndrome. Some teams would outsmart themselves - convince themselves that they should write their own rendering or material system or input handling due to real or imagined flaws in the default offerings, then spend months or years on hard-to-maintain replacements that aren’t any better.

Sometimes a more enthusiastic (some might say naïve) approach works well because when people aren’t aware of limitations they aren’t bound by them.

Sincere Storytelling

The tale of Expedition 33 is more story than lore. It doesn’t begin, as so many games do, with “ten-thousand years ago….” Of course there’s backstory but it’s delivered as events unfold in the present.

That story is a sincere drama. These days characters are often written as if they’re aware that they’re on-camera in a CW show, delivering lines to please an audience in constant, passive-aggressive 4th-wall breaking.

There’s a certain vulnerability in earnestness, as it reveals real thoughts and emotions, rather than safely burying them under layers of ironic detachment. And earnestness just seems uncool at the moment. Thor: Ragnarok allows Thor to feel sad about the destruction of his civilization for two seconds (I checked) before that’s undercut by a joke, and then his entire planet blows up as the punchline. This is a movie disinterested in questions like “how would the characters react in this situation, were it unfolding for real? (I enjoyed the comedy parts but the serious parts don’t work at all)

Expedition 33’s premise isn’t realistic, but given the premise the reactions feel real. Some people are resigned to their fates, while others are miserable, philosophical, or find cause for celebration.

Appropriate Art Style

Much has been made of Expedition 33’s “realistic” art style. I don’t know that I’d call it realistic exactly but I get what that means: you can use assets like Quixel scans (off-the-shelf rock textures) or “Forest Pack 3” with only minor modifications.

I’m wary of broad assertions like “gamers prefer realistic graphics” but I do think “realism” works for the game in a way other art styles might not.

I’ve found myself growing a bit tired of “stylized graphics” and the use of the term “stylized.” You’d imagine “stylized” implies a novel style, but often it indicates a lack of style - more often than not a “stylized” game is attempting to look like World of Warcraft-style Blizzard or the median stylized videogame.

Some stylized looks can be distracting or come off poorly in play. Animating “on the twos” Spider-Verse style, just doesn’t make sense to me in a medium that’s always valued framerate.

More importantly, I think the neutral art style of Expedition 33 plays into one of the game’s biggest strengths: it presents itself as an unknown quantity. You don’t know what you’re getting until you play it.

So much fiction today is IP based, or feels IP-based even when it’s not. Or, barring that, slots neatly into established conventions.

Take a look at one screenshot from The Hundred Line: Last Defense Academy and you know what you’re getting: a cast of wacky one-note anime tropes. At least you think you know what you’re getting, and right or wrong that feeling can nag you for much of the game, even if in the end the game subverts expectations.

In an anime-looking game you expect anime archetypes and plots, whatever that means to you exactly, even if anime isn’t a genre like romance or horror. Gothic Souls-like games, Gears of War knockoffs, etc, also come with certain expectations. Many “adult” games look the same - they use the same Daz3D assets - and many of them play the same4: Ren'Py visual novels with maybe some light sim elements.

Expedition 33’s look doesn’t confer many expectations. That works well with an original plot, and with a genre rooted in exploration and discovery. That’s very different from a game like Atelier Ryza, where despite being unfamiliar with the series I have expectations regarding everything from plot points to character design to voice acting style, based on a few screenshots.

Expedition 33’s combination of plot and art style reminds me of movies like Krull that we don’t get much of anymore. Krull is sci-fi and fantasy but it’s not speeder bikes, blasters, orcs and dragons. It’s its own thing in terms of plot, characters, costumes, locations and sets. It feels, if not unique, at least distinct. Clair Obscur's lack of presentational tells lends it the similar quality of a story unfolding before you, without the broad strokes known in advance.

Hiring for Talent vs Experience

I’m not keen on “hire off of Reddit” but the game industry leans too heavily into credentialism and experience.

Many of the worst hires in my past, both in gaming and in broader tech, share that we were looking for someone with specific experience that our team lacked. We needed a network programmer because none of us were network programmers, for example. It’s hard to evaluate candidates when your team is unfamiliar with the material, and this sort of vaguely desperate hiring can mean bumping a 7 candidate to an 8.5.

Western AAA studios prize experience with other western AAA studios, and often prize genre-specific experience as well. In theory someone who worked on a AAA game has proven chops. In practice it's much trickier; on a large team there are more places to hide and coast by. There’s an idea that someone who’s done the work is vetted - they can use source control, they aren’t an HR nightmare, etc. But as we’ve seen nightmare employees are sometimes actively protected.

The Western AAA MMO space ossified almost immediately, recycling the same members with previous MMO experience. World of Warcraft ate their lunch because, it turns out, being good at making games is more important than having experience making MMOs.

Of course there are certain jobs where prior experience is key. I’ve done short term contracts for porting or game performance - with three weeks to determine why a game runs poorly you can’t hire someone who has to learn performance optimization from scratch.

But if you’re planning on five years of work it’s fine to hire an artist who only knows Blender when you’re a Maya shop. The better artist will, in the long run, be a better hire than the artist who’s better at Maya, and the “long run” is probably months or weeks, not years. It’s fine to hire people with no FPS experience to work on your FPS, assuming your team isn’t totally clueless about the genre. In some cases hires with outsider perspectives may be more creative and less bound by convention.

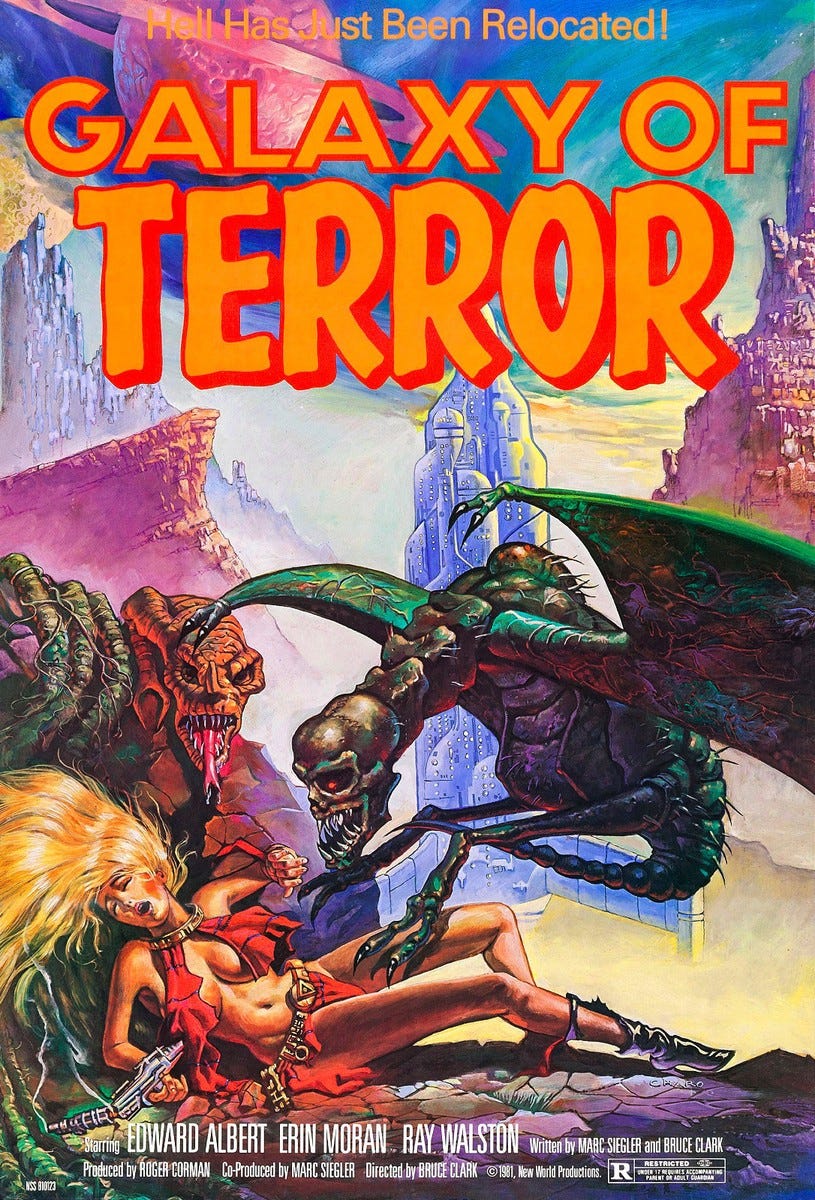

The hiring stories behind Expedition 33 make me think of Roger Corman hiring James Cameron after seeing his short film Xenogenesis. You can find it online - it’s not good exactly but it demonstrates talent. Galaxy of Terror, a Corman film that Cameron did production design on, isn’t a good movie but it’s a good-looking movie, all things considered. Cameron then directed Piranha II: The Spawning. Then The Terminator.

At any point in this chain someone could have passed on Cameron because he worked on hastily-made low-budget productions, didn’t have “real” movie experience, or because the movies were bad.

Many in the game industry would blanch at hiring someone from gaming’s Galaxy of Terror, even if that candidate’s talents were evident to those willing to look. There’s a flip side to that: Expedition 33 didn’t hire many experienced AAA devs presumably due to cost and related factors, but many AAA devs would pass on the chance to work on an Expedition 33 if offered, because it’s not the sort of work experience the industry values.

In Conclusion

I don’t normally provide executive summaries but when in Rome…

There’s a ceiling on how valuable business lessons can be, as these lessons ignore craft, when craft is a (the?) main reason the game did well

It’s human nature to purport to learn what one already knows

Expedition 33 didn’t hew closely to existing business advice - make of that what you will

These guys fucking love Unreal Engine, which is a testament to Unreal Engine but also to the power of enthusiasm

Expedition 33 delivers a sincere good story well told, something many games don’t attempt

In story and presentation it doesn’t immediately invoke a been-there, done-that feeling

Galaxy of Terror has an all-time great poster

In a follow-up post I’ll discuss how Expedition 33 made me confront and change an attitude I held about game design.

Until then…

Or something like that, I don’t know the exact details of their motion capture

Let’s not get too hung up on that number or what “made” vs “contributed to” means exactly.

In fairness, he was let go for a few reasons. See the PsychOdyssey videos for more

Based on my extremely limited research of course

This is great. Feels fresh, sincere, multi-vector in its approach and conclusions. Subscribed!

"Sometimes a more enthusiastic (some might say naïve) approach works well because when people aren’t aware of limitations they aren’t bound by them." - excellent, corresponds with Orson Well's self-professed 'ignorance' that he embraced when producing Citizen Kane.